When pushing work at an Actor, there are many times when it might not even get started before the guy that asked for it completely loses interest. How do you make sure that you don't start work needlessly?

I was talking to some guys recently about how they should handle a particular aspect of their workload with Akka. They had designated a certain group of Actors as workers that would execute a relatively long running operation and return the result to the caller.

They were having the classic problem of dealing with timeouts. The work piles up to the point that a caller has given up on getting the result, but the worker doesn’t know that, and performs the work anyway. This is just a waste of CPU, and it means that every single queue job is going to take longer and longer, needlessly.

I told them to do something along the lines of what I’m presenting here.

Aside - How (not) to Queue Work

First of all, they were using the Actor’s mailbox to queue up their work, and I never recommend that you do that. The mailbox is the communication channel between your Actor and the outside world, and it sucks if you start plugging it up with a bunch of messages, because it’s a FIFO. What’s more is that the mailbox itself is pretty opaque to you; it’s hard to look inside it and see how full it is, or selectively order what work is in there, or whatever else you’d like to do.

You can create your own mailbox but I advise against that - not because it’s hard to do, or buggy or anything like that - simply because it’s simpler to use Akka’s default implementations for things, let them do the awesome things they do, and write separate abstractions to handle the logic you need to handle.

A basic principle of Actor programming is that you should constantly be striving to empty your mailbox as fast as possible. If this means you empty it for the sole purpose of queueing work in an auxilliary queue, then so be it. Empty that mailbox as fast as you would when the new issue of Playboy is due to be delivered (didn’t think I knew, did ya?).

That’s the essential aspect of queueing work, forgetting the details of the code. Don’t use the mailbox to do it - use a queue.

Back to the task at hand

So, how do we alert the worker that the caller is no longer interested? There are two basic mechanisms that we could employ, and I’m going to call them the active and passive methods.

- Active: The caller actively tells the worker that he’s no longer interested and then ignores anything that might happen from then on out.

- Passive: The caller spins up a proxy that takes care of the effort of cancelling the work. The caller ignores the responses from the worker, and the proxy is in charge of telling the worker it’s not interested in results when the worker asks.

I’m going to use the passive approach because I like it better today. The active mode requires more messing around with the queue, and if I want to collect some stats about how long things “might take” then I have to have two data structures - one that carries the work to be done, and another one that holds the information about guys that don’t care anymore. Then, when the work is to be done, I could scan the second data structure, know that it doesn’t need to be done, and the report on how long it took to get there.

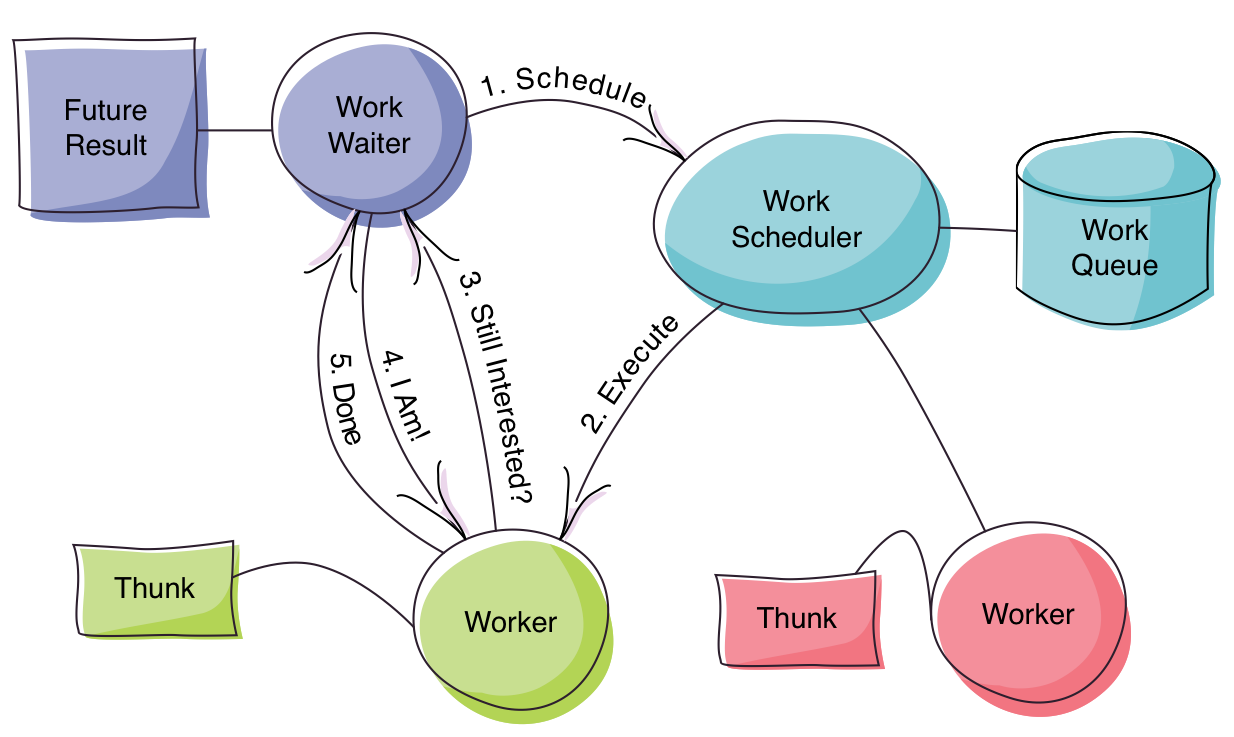

I just don’t wanna do that stuff, so I’m going to solve it the passive way and use Actors. It’s gonna look something like this:

The Future[Result] comes from the following method call, and is really the API that you’re going to expose, forgetting all of the interesting complexity in that diagram.

def doTheWork(work: Work)(implicit timeout: Timeout): Future[Result]

You can see from the diagram, and that method, that the Result value is coming through in a Future and between that Future[Result] and the Worker that’s actually running the code, there’s a WorkWaiter that’s just sitting there waiting on the Worker. When the Worker comes around to actually do the job, he’s going to check with the WorkWaiter to see if he should proceed. It’s possible that the WorkWaiter has already completed the Promise with a failure due to a timeout, in which case the WorkWaiter isn’t interested in the result any more and the Worker can fail fast.

Let’s start with how that API function hooks in to the WorkScheduler:

class TheApi[Work, Result](factory: ActorRefFactory, thunk: Work => Result, concurrentLimit: Int = 5) {

val workScheduler = factory.actorOf(WorkScheduler.props(concurrentLimit, thunk))

def doTheWork(work: Work)(implicit timeout: Timeout): Future[Result] = {

val promise = Promise[Result]()

val ref = factory.actorOf(WorkWaiter.props(work, workScheduler, promise, timeout))

promise.future

}

}

TheApi spins up a single instance of the WorkScheduler with a maximum concurrency limit (i.e. the maximum number of workers to have running at any given moment) and a thunk that will execute the work when called upon. So, when we call doTheWork(work) the Promise / Future bridge can be created, the WorkWaiter can be started and he can send the work to the WorkScheduler.

So far, so good. Let’s jump to the WorkScheduler to see what it does:

class WorkScheduler[Work, Result](concurrentLimit: Int, thunk: Work => Result) extends Actor {

// No big deal, just start the worker

def spawnWork(job: Job[Work]): ActorRef = context.watch(context.actorOf(Worker.props(job, thunk)))

// Rather than have internal `var`s, I've opted for closures

def working(queue: Queue[Job[Work]], runningCount: Int): Receive = {

// We haven't reached our maximum concurrency limit yet so we don't need to queue the work

case QueueWork(work: Work @unchecked, recipient) if runningCount < concurrentLimit =>

spawnWork(Job(work, recipient))

context.become(working(queue, runningCount + 1))

// We're already running at our maximum so we queue the work instead

case QueueWork(work: Work @unchecked, recipient) =>

context.become(working(queue.enqueue(Job(work, recipient)), runningCount))

// One of our workers has completed, so we can (potentially) get something else running

case Terminated(ref) =>

queue.dequeueOption match {

case Some((job, q)) =>

spawnWork(job)

context.become(working(q, runningCount))

case None =>

context.become(working(queue, runningCount - 1))

}

}

def receive = working(Queue.empty, 0)

}

There’s nothing earth shattering here; the WorkScheduler either queues up or executes work inside of Worker Actors. The only real complexity in there is that it manages the maximum allowed concurrency.

Let’s move on to the Worker itself:

class Worker[Work, Result](job: Job[Work], thunk: Work => Result) extends Actor {

import context.dispatcher // implicit EC

implicit val _timeout = Timeout(5.seconds)

// First we need to understand whether or not we should even do this.

// In every case, we're going to get an answer, which will ensure that this

// Actor terminates, assuming the thunk terminates.

job.recipient.ask(AreYouStillInterested()).map {

case IAmStillInterested() =>

Proceed()

case _ =>

ForgetIt()

} recover {

case t: Throwable =>

ForgetIt()

} pipeTo self

final def receive = {

// The recipient is still interested, so let's do it

case Proceed() =>

val result = thunk(job.work)

job.recipient ! WorkComplete(result)

context.stop(self)

// For whatever reason, we're going to be doing this work for no reason,

// so let's not do it.

case ForgetIt() =>

context.stop(self)

}

}

Now we see the passiveness of this solution. The Worker hasn’t been told that the recipient is no longer interested; instead he asks whether or not the recipient is interested.

We could have asked in the WorkScheduler but consider that solution for a moment. If the WorkScheduler is going to perform the ask then he’s going to be doing so asynchronously, and between the time he asks the question and the time he gets the answer, many other events could occur. This means he’s going to have to change to a different state where he understands he’s got a pending request to start something. In this new state he knows that he’s potentially running another job and so he can manage his concurrentLimit accordingly.

That’s a pain… the solution? Delegate the annoyance to another Actor where it can be managed much more simply.

Now, let’s have a look at the WorkWaiter, which is really the most important part of this solution:

class WorkWaiter[Work, Result](work: Work, workScheduler: ActorRef, workResult: Promise[Result], timeout: Timeout) extends Actor {

// Set the timeout to ensure that we can (potentially) fail the promise appropriately

// Schedule the work with the work scheduler

override def preStart(): Unit = {

super.preStart()

context.setReceiveTimeout(timeout.duration)

workScheduler ! QueueWork(work, self)

}

def interested: Receive = {

// We were interested, but didn't get the answer in time, so we're not

// interested any more.

case ReceiveTimeout =>

// We don't need another ReceiveTimeout

context.setReceiveTimeout(Duration.Undefined)

// Fail the result, cuz it's just too late

workResult.failure(WorkTimeoutException(timeout, work))

context.become(notInterested)

// Great! We got the result in time so we can produce the happy ending

case WorkComplete(result: Result @unchecked) =>

workResult.success(result)

context.stop(self)

// Since we're in the `interested` state, we're definitely interested

case AreYouStillInterested() =>

sender ! IAmStillInterested()

}

def notInterested: Receive = {

// Too bad. We were interested, but the work didn't finish in time so

// the only reasonable thing we can do is discard this

case _: WorkComplete[_] =>

// Nope, we're not interesed so don't bother starting

case AreYouStillInterested() =>

sender ! IAmNoLongerInerested()

context.stop(self)

}

def receive = interested

}

Remember that, if the ReceiveTimeout has been reached, the Future[Result] gets completed immediately, so the ultimate client isn’t left hanging around. It’s the job of the WorkWaiter to hang about and furnish the Worker with the information it needs.

Conclusion

This solution doesn’t help you cancel work that is currently in progress. That’s only possible if the thunk that’s working is something you can appropriately cancel and in my client’s case, it wasn’t possible. What this does is allows you to not start work that would be needless due to the caller’s lack of interest in the result.

I’ve solved the problem using more Actors than one might expect. This passive approach may be thought of “inefficient” due to the spinning up of a Worker for no reason, and the hangabout of the WorkWaiter for longer than you might think is absolutely necessary. I don’t care for a couple of reasons:

- It’s “simple” in that it leans on messages and ephemeral endpoints more than complicated data structure manipulation.

- The time it takes to spin up these Actors and to handle the simple protocol is absolutely irrelevant in the face of the “long running” thunk.

This solution keeps the concurrency and asynchrony fluid and solves the original problem.