There are times when you need to assemble a bunch of work, or gather a bunch of state before moving things on to "the next stage". Since things can fail, you might need to restart or give up. How do you handle the information that's not-yet-complete? Throw Actors away!

(This post relates to Akka 2.3.11)

We’ve had a lot of problems with Akka Remoting, especially as it couples with Akka Clustering because the Akka transport isn’t terribly friendly with clustering or with remoting in general. That’s quite a loaded statement, and it deserves a quick explanation lest I appear to be unfair.

The Issue with Akka Remoting and Clustering

The Akka network transport is a single TCP pipe that exists between two Akka nodes. This singular pipe is shared amongst all aspects of Akka that require communication between nodes in the cluster. This means that “system level” or “cluster level” messages must fight for control of that singular pipe.

Now, it should be noted that there are two distinct queues in the remoting subsystem that favour “important” messages. If the system queue has anything in it, then that queue will be flushed before the “user” queue is looked at. However, if the current message in flight is a user message, then the system queue is going to sit there doing nothing.

That’s not so bad, but the transport doesn’t automatically chunk the messages up into bits and pieces. So if you end up sending lots of big messages (unbeknownst to you, in many cases) then you clog up the works.

The remoting heartbeats and the cluster heartbeats travel along this singular transport and at the default configuration, we experienced a ton of lost nodes in the cluster. We had to set the various acceptable-heartbeat-pause values to 45 seconds in order to survive the issues that would come up.

The answer to the problem, according to the Akka team, is to not use the remote transport. I find this to be a hard answer to swallow, but arguing the point doesn’t fix my problem :)

Don’t get me wrong, I still love Akka. :D

How I’m Getting Around It

I’ve taken two approaches to work around this problem:

- A poor man’s streaming implementation

- Building my own remoting, with automatic message chunking to ensure fairness.

I’m still working on number 2) but number 1) was a fun exercise and there’s an aspect of the solution, in particular, that is the topic of this post.

Streaming

The biggest culprit in our software that causes the problem is the result of a query. An Actor in one node can make a query to an Actor in another and the size of the resulting payload is entirely arbitrary. It can be a few kilobytes to a ton of megabytes. However, in any case the payload can be broken up by “row”. Essentially, the resulting payload is a “table” consisting of N rows that are all “small” in size.

At the time of writing, Akka Streams was not capable of sending data across remoting so it was not a viable solution to the problem, and this is why I built my own.

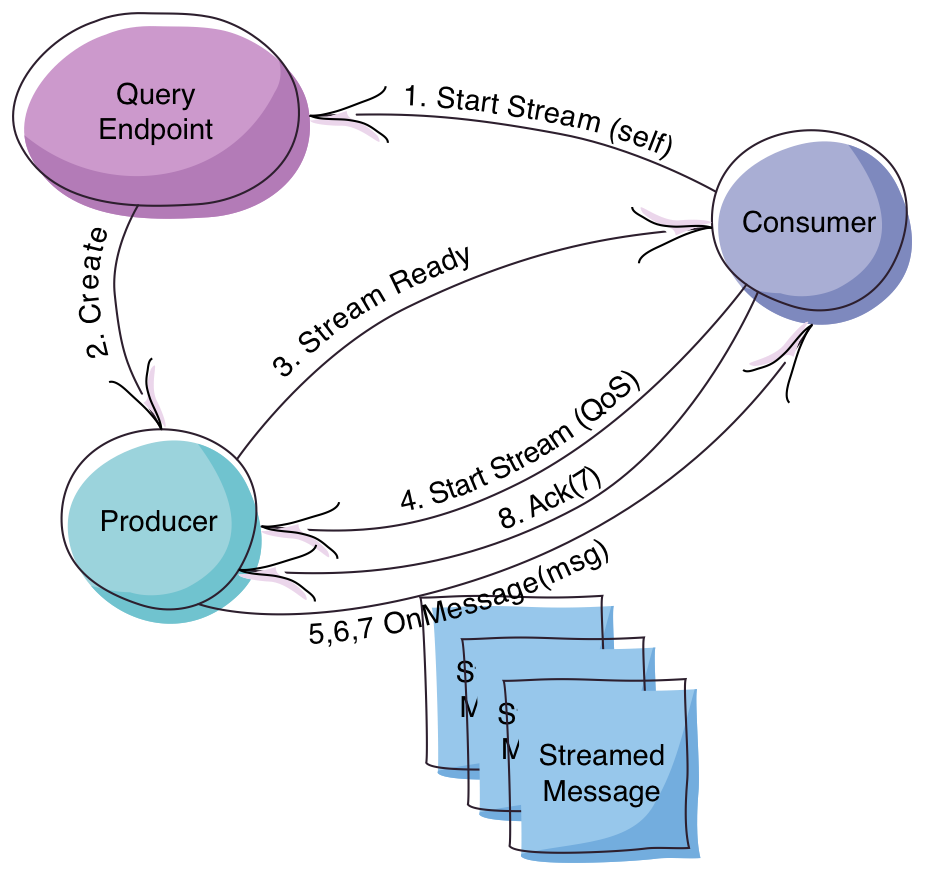

Effectively, that’s it. You’ve got a Query Endpoint, which is where the Consumer is going to make the query, which is going to set up the Producer, which iterates over the data, sending each piece of the data to the Consumer adhering as well as it can to the specified quality of service. The Consumer will Ack the messages when it can - it doesn’t Ack each one individually, but only Acks the highest thing it’s seen. This keeps the chatter down.

Note that all of this is still going over the existing Akka transport.

Oops

Each message gets a sequence identifier so that the Consumer can ensure that it hasn’t missed anything. But what if it does? (The odds on this are crazy low, but I’m not building something at the top of the architecture here… this is the bloody message transport, so I need to make sure)

Let’s say the Consumer has requested a QoS that says it allows there to be 20 unacknowledged messages to be in-flight at any given time. The Consumer gets message 1 and then message 3; it needs to fill in the gap in its history. What are some approaches to doing this?

- Have the

Consumercontinue to consume incoming messages. For every one that is lost, request a resend on that message.- When he receives message

4, he sees another gap (“Hey, where’s message2?”) so he has to remember that message2has already been requested as a resend - Eventually he might need to ask for

2again, if he doesn’t get it. - The

ProducerneedsAcks, right? We’ve said that we’re going toAckthe highest seen thing, in order to be less chatty, but now what? TheProduceris going to want anAckfor2eventually, but it’s not the highest we’ve seen at that point.

- When he receives message

- Toss the state and start where we left off.

Remember, we’re talking about corner cases here. Why muddy up a protocol, muck with managing the internal state of an Actor, and potentially reduce performance for these rare conditions? Don’t.

So, we opt for the second solution.

Resending

Let’s add something to the protocol:

// Why the `resendTo`? There's a hint above, but if you didn't see it you'll see it soon

final case class ResendFrom(msgId: Int, resendTo: ActorRef)

Now, the Consumer can say producer ! ResendFrom(2, self) and the Producer can oblige. However, we’ve got another problem… the Consumer’s mailbox may have 17 more messages sitting in it. What’s it going to do? It’s going to see message 4 and then 5 and so forth. The basic logic will demand that it send a ResendFrom(2, self) to the Producer for ever message it sees that’s not 2. That’s gonna suck.

So what’s the pragmatic approach? Abandon that Actor!

If we have the Consumer delegate the act of gathering the messages to a child, recognizing that the child may have to deal with some volatile materials, then we can abandon it at will. Yeah, it’s got stuff in its mailbox that we could use but we’re not optimizing for the corner cases. So just let the dude die.

class StreamGatherer(seenSoFar: Int, subscriber: ActorRef) extends Actor with ActorLogging {

import ActorSubscriberMessage._

context.setReceiveTimeout(aReasonableTimeoutDuration)

def system = context.system

var highestSeen = seenSoFar

def expectedNumber = highestSeen + 1

def receive = {

// Awesome. We're done. Tell the subscriber

case OnComplete ⇒

subscriber ! OnComplete

// Oops. Let the subscriber decide what to do

case msg: OnError ⇒

subscriber ! msg

// Happy days!

case msg @ OnNext(StreamedMessage(n, _)) if n == expectedNumber ⇒

highestSeen = n

subscriber ! msg

// We've got a problem. The message we were given didn't have the

// expected sequence number. We're screwed

case OnNext(StreamedMessage(n, _)) ⇒

log.warning(s"Received message $n when we expected $expectedNumber. Requesting resend from $expectedNumber")

subscriber ! Resend()

// Become dev/null in order to drain off the excess

// The subscriber (the guy that's using us) will

// stop us when he sees we've had this hiccup

context.become(devNull)

case ReceiveTimeout ⇒

log.error(s"Timeout while waiting for more input from upstream.")

subscriber ! ReceiveTimeout

context stop self

}

def devNull = Actor.emptyBehavior

}

That’s the meat of it. The Consumer is going to create the instance of the StreamGatherer, telling it where it’s starting from, and it’s the StreamGatherer’s job to relay the messages back to the Consumer. If the StreamGatherer sees that it’s in a bad way, it will immediately siphon off the remaining messages in the mailbox, ensuring that there are no odd side-effects to what it sees.

Let’s take a quick look at the important bits of the Consumer, just to see how it ties together.

class PoorStreamConsumer(...) extends Actor {

var highestSeen = -1

/**

* "Cycles" the current gatherer. Stops it and creates another one in

* its place. The state inside the existing gatherer is lost, which is

* exactly what we're going for.

*/

def cycleGatherer(oldGatherer: Option[ActorRef]): ActorRef = {

oldGatherer foreach { g ⇒

context.unwatch(g)

context.stop(g)

}

val gatherer = context.actorOf(gathererProps(if (oldGatherer.isDefined) highestSeen else -1, self))

context.watch(gatherer)

gatherer

}

def waiting: Receive = {

case StreamReady(producer) ⇒

context.watch(producer)

val gatherer = cycleGatherer(None)

// Note that we subscribe the `gatherer` to the stream, not the subscriber!

producer ! StartStream(maxInFlight, maxBytesInFlight, gatherer)

context.become(stream(producer, gatherer))

case // Handle some errors too =>

// With error handling logic

}

def stream(producer: ActorRef, gatherer: ActorRef): Receive = {

case OnComplete ⇒

// Do the finising stuff

case OnError(reason) ⇒

// Do the error stuff

case OnNext(StreamedMessage(n, el)) ⇒

// We got the next message happily

case Resend() ⇒

// The gatherer has told us that we need to get the producer

// to resend the stream from the highest thing we've seen. So

// we cycle the gatherer and tell the producer to do just that

// ensuring that it sends the payload to the new gatherer

val newGatherer = cycleGatherer(Some(gatherer))

context.become(stream(producer, newGatherer))

producer ! ResendFrom(expectedNumber, newGatherer)

case // Handle some errors too =>

// With error handling logic

}

def receive = waiting

}

I’ve left out a lot of the details of errors and real-life issues because, well… that’s just noise. The upshot is that the Consumer is subscribing the Gatherer, not himself, to the Producer’s stream. This keeps the Consumer’s internal state pristine, not having to deal with the nonsense of in-flight state or retries or these annoying things. If the stream gets corrupted, then he cycles the Gatherer and gets the Producer to resend its stream from the last known point, ensuring that the Producer sends the stream contents to the new Gatherer.

Conclusion

The Actor can naturally be a spot that holds ephemeral state. Sometimes maintaining this state can be a royal pain in the ass, but the beauty of the Actor is that it has a life-cycle and we can terminate it any time we like, bringing up a new one in its place.

In many ways this is the essence of the actor design philosophy. Stateful Actors should be short-lived, and it’s the messages that matter. Sure, there are lots of cases where you have to have lots of stateful Actors and they’ve gotta have long life-spans, but that sucks. Don’t do it if you don’t have to. Concentrate on the messages and the protocol, carrying the state in that whenever possible, and just let your Actors die.